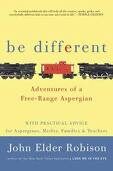

John Elder Robison is as fascinating as you might imagine; bright, articulate and thoughtful. His first book Look Me in the Eye: My Life with Asperger’s became one of the most popular works to introduce people to autism. He thought he would write a second book because he realized that people had such a strong desire for insight. Be Different: Adventures of a Free-Range Aspergian With Practical Advice for Aspergians, Misfits, Families & Teachers

is filled with stories he says “show how every component of autism that you find in the DSM manual affects my life. Some of those things help me to be successful, and some of those things hold me back, so it’s a mix, all those different traits.”

Your new book is Be Different, then you use the term “Free Range” in the subtitle. Are you describing a time before diagnosis?

I grew up without being constrained by any kind of diagnostic label. On the one hand, it’s good that kids get diagnosed and they get special assistance in school. But for me, it was also good that I did get held to the same standard as everyone else, and I had to just make my way in the world.

Did you feel a sense of relief when you got the diagnosis?

Well, it was tremendously liberating and empowering because people had called me names, and I had always perceived myself as defective … I didn’t know what was different about me but I could see that there was something the matter with me because other people had all these social success and I didn’t.

Well, it was tremendously liberating and empowering because people had called me names, and I had always perceived myself as defective … I didn’t know what was different about me but I could see that there was something the matter with me because other people had all these social success and I didn’t.

So for me to read about Asperger’s and to realize that I wasn’t defective and I was a part of this community … I had a poor self-image all these years and then to take the knowledge of how Asperger people are different than other people, gave me insights for the first time, as to how I might change my behavior to make myself more acceptable to other people. And it worked, and that was a really big deal for me.

You say, “I am a person with Asperger’s, or you are an Aspergian or an Aspie. I say my son has autism, or he is autistic, interchangeably, but is there a way you think we should talk about it? Is that language important to you?

I think you have to sort of careful of that when you say “He has autism.” Careful that people don’t get the impression that it’s like saying that he’s caught the flu or that it’s a temporary condition that is going to go away. Because, of course it isn’t going to go away. It’s a state of being more than a disease you have.

Like when people say my son is “so much better” from the last time they saw him?

Yes, because he’s really developing. Most people with any kind of autism learn coping strategies that work progressively better as we get older. So you will always have the same autistic differences in your brain that you were born with, but people will emerge from disability to varying degrees. Some people will always have a significant degree of disability and will require services, whereas other people who were pretty disabled as children might not be disabled at all as adults. I’m an example of that.

The label autism describes you, an accomplished author, family man, and entrepreneur; and also my son who is non-verbal and has very few self-help skills — and all those in between. How do parents like me keep looking for answers, solutions, and ways to help our children without offending adults with autism? How does a parent occasionally grieve a missed milestone because our child is disabled without somehow implying that your part of the spectrum is defective and not just different?

I think that the really big issue in the world of autism comes down to one of the principal components of autism: our diminished ability to put ourselves in the other person’s shoes, or recognize other points of view as valid. So any person who is personally touched by autism is going to have a greater predisposition to think that autism for everyone is the way autism is for him. The result is that people who are highly verbal tend to think “Well, people in the autism world don’t need any kind of research or medical assistance, they just need society to accept us.”

And then they make the leap to the idea that anyone who does do medical research is just engaged in trying to get rid of us; which is not true. Then the people who have kids with pretty severe disability they tend to dismiss those with less visible disabilities.

When the truth is that both groups of people need support and services?

One of the leading causes of death in those people who can’t care for themselves is neglect, misadventure, and accident; those are all preventable deaths. The CDC is advocating a diagnostic code for people who wander as a result of severe disability so we can get services to keep those people from going out in the street and getting killed by cars. Now there’s opposition to a notion like that by people who think that it would just be a tool to restrain an individual who just don’t do what others say. But it’s really a concept to address a significant cause of death.

And then if we look at those people who are supposedly high-functioning and verbal, they’re the ones who commit suicide. They’re the really bright kids, who couldn’t seem to fit in, and no one understands why they would do it.

The truth is that autism can be deadly at the two extremes, and I hope that people recognize that both ends of the spectrum are equally deserving of services — but the services they need are very different.

I was fascinated by your appearance in the Discovery Channel’s Ingenious Minds documentary. Tell us about your experience with Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, or RTMS. Were you scared?

It isn’t scary at all. They did a number of stimulations where they delivered electromagnetic energy to different small areas of my brain in an attempt to temporarily rebalance those areas, and see if the changed balance will allow me to see non-verbal signals from other people more effectively. We did twenty stimulations and of those twenty, three had powerful transformative effects.

Was the effect lasting?

The effects of the stimulation were temporary, but it’s as if you grow up color blind and all you see is the world in black and white. And all your life people have been saying to you, “Her shirt is red.” and, “He’s got a green coat on.” And you know those two people look exactly the same in your black and white vision, so when everyone keeps saying “that’s red” or “that’s green”, eventually it just makes you mad.

And when you start to become angry hearing that, it’s what you might call a maladaptive behavior because you are using the incorrect evidence of your eyes to draw a wrong conclusion.

Then, imagine you go into a lab, they do something and it flips a switch in your mind. And you walk out of that lab and you can see red and blue, and all of a sudden you know that what you been told all your life was true and that it was your perception that was the lie.< And that ability fades away, and you go back to seeing in black and white but your world is changed forever because you know that the configuration exists in your mind to see color, and you know color is the true story not black and white. That’s sort of what’s happened to me. The stimulation had an effect that was temporary, but it showed me that my mind has the ability to perceive these things. I’m teaching myself to do it. You might say that I’m willing myself to use those pathways. The TMS didn’t make new paths but illuminated what was there.

Do you visualize it like that?

I sort of visualize like that and people say that I have this extraordinary ability to reflect upon things, so it’s possible that it allows me to get a value from TMS that someone that doesn’t have that self-reflective power might miss.

Do you recommend it to perhaps the other end of the spectrum?

I don’t recommend it for anyone right now because it’s not a therapy, it’s scientific research, which I believe will ultimately lead to therapies. What the TMS is showing, is that the wiring in the brain to “fix” some of these components of disability may already exist. For example, your son may already have wiring in his brain to talk, so if we have the ability to suppress what was holding that back we might be able to then give him more ordinary power of speech. That’s potentially a very powerful thing, and that’s the ultimate goal of this research — but they have a long way to go before it moves from experimentation to therapy.

The word “fix”, or “cure” can be a little dangerous to use, no matter who you’re talking to. Do you think there might be a backlash? Or would it be hard to deny that this is a positive benefit?

Backlash? I am fully aware of the difference between what someone might call a cure for autism, which in my opinion, is not a realistic thing to think about. If you have a difference in your brain, and you grow up with that difference, your brain has wired itself in the image of what it has experienced. You can’t just take a part of that out. But we could change your son’s life if we had a tool that could help him talk. It doesn’t mean we cure autism, we would just be helping your son to talk, and he would have a better quality of life.< When you look at this as having the goal to develop tools and therapies to remediate or fix certain components of disability, I can’t imagine how any reasonable person would be opposed to that. If we develop a tool that helps an autistic child to talk. If you’re a person with autism who does speak, than that tool is irrelevant to you, but it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be able to recognize the enormous value it has.

One of the many quotable phrases from Be Different is “Competence excuses strangeness.” Do you think employers provide enough accommodation for people who think differently?

I think one thing we can do is have employment screening that looks at alternatives to traditional college credentials. For example, in the world of engineering I have demonstrated by my accomplishments that I would be a good person to hire in a lot of technical companies, and I don’t have a diploma. One thing that would be a major step would be for employers to become more open to accepting alternate credentials from potential employees in the same way that colleges give life experience towards a degree.

The screening process doesn’t really catch those people now?

There are some technology companies who recognize this. I hear, “A person like you would be an ideal employee. How would you have gotten in the door if you were twenty-five today?” They recognize that their screening tools are potentially screening out good workers. There’s an awareness. The next step would be a desire to change.

Thirty years ago you couldn’t demonstrate how you could make a contribution to a company if you didn’t already have access to that company’s proprietary software, but we’re moving towards an “Open Source” world. Right now a sixteen year old who is brilliant at software but failing at school can go out there and code, and can bring himself to the attention of an engineering team at a company like Google.

What other advice would you give Aspergian teens about relationships?

My advice in Be Different is to make yourself choosable. For a guy to go out and on the offensive trying to select people and befriending them, that requires a level of social understanding that we may not have. It’s much easier to choose to just act in ways that makes us choosable, instead of ways that makes us repellent.

Sounds like good advice for most people.

If I am polite, open doors, and am considerate, people will talk to me. People will appreciate me and I will not have a bad outcome. This is perfectly typified in the movie Being There with Peter Sellers: if you are just quiet and polite, a lot of opportunity will come your way.

So are you saying to squash your personality?

People ask if I am proposing that we become false, and I’m not saying that. If someone walks into the room and you think she looks pretty, then by all means tell her, she’ll be happy. But if you think she looks ridiculous in that striped shirt, don’t say that. You need to teach yourself which comments will get a good response and which will generate a bad response and you need to think before you say things. I’m not saying make up a lie, or tell her she looks beautiful when she doesn’t.

So it’s almost just using a filter? You decide which observations you share?

Yes. It’s fine to have those thoughts, you just need to learn which thoughts you can articulate to a wider audience without bringing disaster upon yourself.

It’s a logic filter, and these are things that do not depend upon subtle abilities to interact with or read people. It is a rule- and logic-based system. Before I make a comment, does it pass this test? And if the answer is “no,” I don’t say it. That’s not being untrue; that’s learning how to conduct yourself in a way that will work. Sometimes by keeping your mouth shut, you stay friends with that person, and then you have a chance for positive interaction in the future. If you alienate the person, you’ve failed, because your future opportunity for interaction came to an end.

Ideally, you’re only being neutral or positive. I think that it’s a significant piece of advice for anyone, but especially appropriate for people on the spectrum because we don’t naturally possess a filter. Nyptical people very often lie and say “oh don’t you look sweet today.” when they don’t mean it. That’s false behavior in order to take advantage of someone for something. I don’t advocate that at all.

It’s Autism Awareness Month. What does that mean to you? If there was one thing you want people to know about autism, or take away, or feel, what would it be?

I don’t have a “one thing” I want people to know. No one sentence answer.

Autism Awareness Month is sort of like Black History Month I suppose, where people who would not otherwise have any connection are made aware that the topic exists. And I think for many, many people who are not connected to autism it’s not something they think about at all. So if by having Autism Awareness Month we make some people aware in some way, then that’s a constructive and good thing.

We want to make people aware. Autism is an important part of our culture. We want people to find out more. In the last decade we have created a general awareness, so that if you just stopped someone on the street and asked, “What is autism?” most people could give you some answer that was sort of close to correct. That’s a major accomplishment.

—-

Mr. Robison is currently on a book tour. Those of you in the SF Bay area can see him:

April 18, 2011, in Sebastapol at Copperfield’s 138 North Main Street at 7pm. Call Copperfields at 707-823-8991 for more information.

April 19, 2011, in San Francisco at 7pm for a free public event at Books Inc.- Opera Plaza in San Francisco. For more information, contact Margie Scott-Tucker 415.643.3400 x11

For more book tour information, please see John’s blog.