Rivka Iacullo

netiimvzaviyos.livejournal.com

My son CJ is now five years old, coming up on six. He’s a bright boy who loves reading (though he doesn’t like demonstrating his skill on command), tow trucks, playing outside, and the color orange. He spends hours on the weekends enacting strange and elaborate imaginative scenarios with his younger sister Claire, who functions as his trusty sidekick. (One of their favorite games is “Princess and Customer,” something I could not make up myself if I tried.)

CJ was diagnosed with autistic disorder at the age of three. He is sufficiently high-functioning that it took me a while to wrap my mind around the possibility of autism. This is, I believe, at least partially because of the incompleteness of the short autism awareness blurbs that show up in parenting magazines, pamphlets in the doctor’s office, and the like. They recommend action when children don’t talk, never make eye contact and spurn hugs and physical contact. They don’t tell you what to do when your child talks but uses language in unusual ways, makes eye contact (though intermittently) and begs for tickles and tight hugs. Plus … my kid? The one who met all of his early gross motor milestones on time? Who makes sure my husband and I are looking before doing things to make us laugh? Who started talking on cue right around his first birthday? (His first word was “that.” It was a command for me to identify whatever he saw. He would point to objects and demand, “That!”) Who learned the alphabet before his second birthday?

But there came the day not long after he turned three when I felt like I could no longer avoid certain questions, and I finally allowed myself to read the DSM-IV criteria for autism. Upon seeing those words, I felt like I was going to faint or throw up. Nearly everything I had been secretly wondering about was there: lack of conversational language, pronoun reversal, never asking questions or requesting things, pointing out objects of interest for his own reference but never to draw someone else’s attention, constant quoting of cartoons or overheard conversations, intermittent (and decreasing) eye contact, difficulty connecting to kids his age, limited imaginative play, obsessions with certain routines and things (especially trucks, and more particularly their wheels), toe walking, hand- and arm-flailing, extreme resistance to toilet training.

Initially, I felt like the shock and fright would drown me, and I spent the better part of a week yelling at G-d whenever I had a moment to myself. But it didn’t last. There were a few thoughts that took hold in my mind very quickly:

- This is the same child I have cared for and loved for more than three years. The word “autism” doesn’t change that. It just gives me a name for this situation.

- Speaking of which, I am secretly relieved. I wasn’t off base when I kept wondering why parenting him seemed so much more confusing and tiring than it “should.”

- He doesn’t need to be fixed; he needs help in ways I didn’t anticipate.

Even before we got a diagnosis, we set about looking for that help. And thank goodness, we were lucky enough to find a succession of kind, dedicated, patient, and skilled therapists and teachers who offered practical help and not snake oil. I credit these fine people for engaging with him in ways that motivated him to work on his language, sensory, and fine motor challenges, and I credit him for his persistence (and frequent joy) in working on the same things.

So here we are, coming up on three years since I let myself read that section of the DSM-IV and two years since the delivery of an official diagnosis of autistic disorder. And yet one of the best examples I can come up of what autism has meant to us comes from a time before we started down this path — before we knew it existed, really.

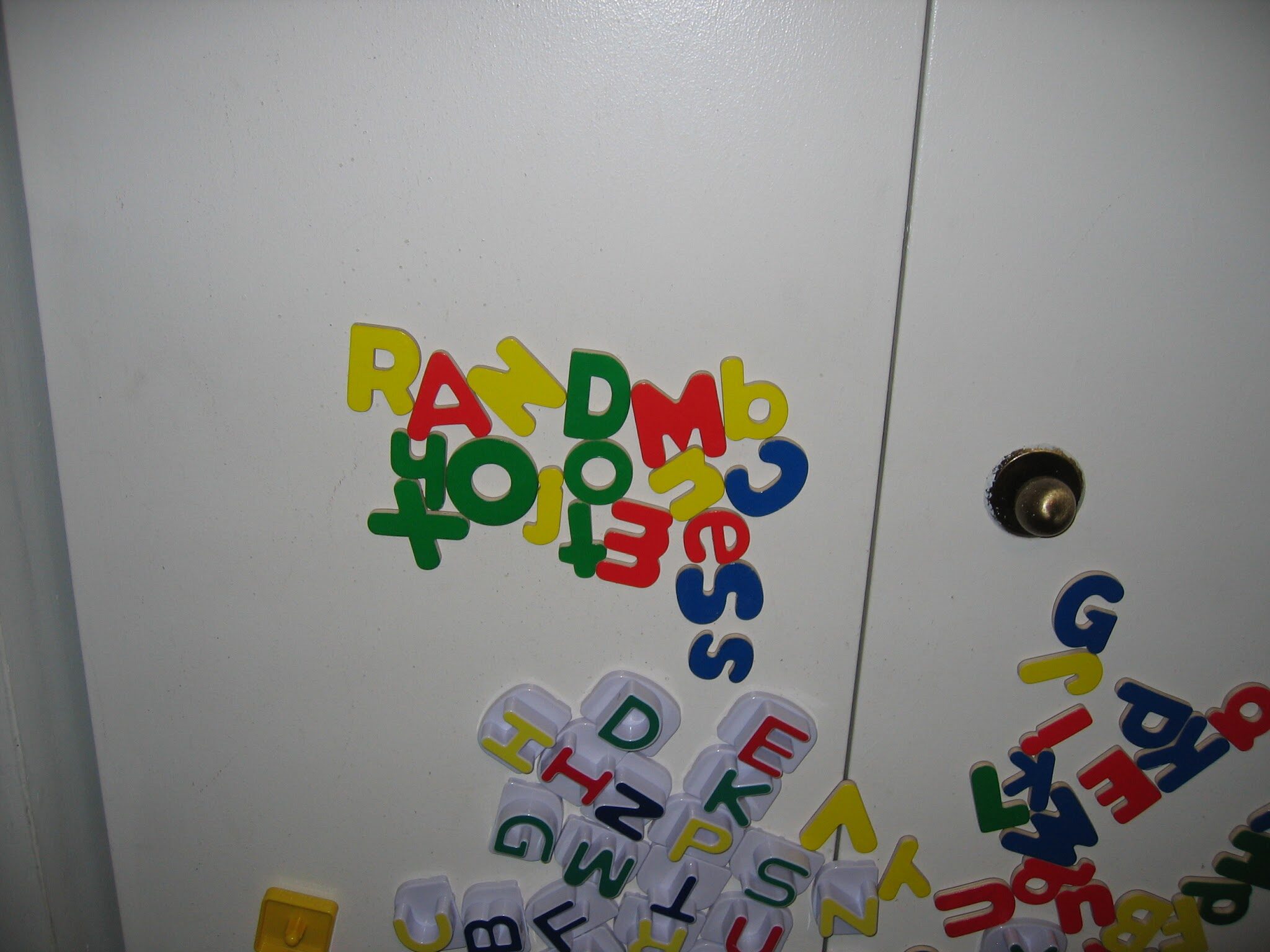

Shortly after CJ turned two (I think), he started lining toys and other things up, laying them out in sinuous, curving streams. His favorite subjects for this were his toy cars and the magnetic letters on his closet door. Not long after that, he started fashioning more complex structures. He’d pile toys up into elaborate three-dimensional stacks and carefully position magnetic letters into clusters that I thought of as “jumbles.” This happened before I was in a position to read anything into his behavior, so I just marveled at the weird and wonderful things he came up with, such as the time he moved most of his possessions into a couple of large concentric rings that my husband Walt and I dubbed “Toyhenge.” (That was really something to behold. It took him two or three hours to arrange, and we both agreed that there were patterns at work that we could sense but not quite define.)

Walt got into the habit of peeking into CJ’s room when he first got home from work in order to see whether any words had appeared. We did spot a few three-letter words here and there, and on one occasion we found a four-letter word, “kiss,” at the beginning of one long, snaking line. We figured the words were random. CJ had learned the letters of the alphabet shortly before his second birthday but hadn’t, so far as we could tell, progressed to putting them together.

One day, Walt came home and as usual popped into CJ’s room. I didn’t think anything of it until he called out to me, saying that there was something in the room I needed to see. He had an odd, vaguely worried note in his voice. I figured it was something involving a soiled diaper and went in.

Walt pointed at the closet door to a jumble of letters. “Do you see that?” he asked. His face had gone pale.

I looked. I started at the top left and looked across. R-A-N-D, I thought. Hmmm. Oh, there’s O-M, down and then to the side. R-A-N-D-O-M. Oh wow, that’s – wait. Is that … ? Yeah, it is. N-E-S-S, down under the M. Randomness. How in the world did he do that?

I narrowed my eyes at Walt. “Did you do this?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “If it had been me, I would have written something dirty.”

We both stared at the closet door, feeling unsettled and awed and confused all at once. Randomness.

That’s right, randomness. Not just a word, not just a long word, but a word that was a comment on itself.

And that is what living with CJ is like sometimes.