Shannon Des Roches Rosa

“Stress is involved in almost every incident of serious child abuse, but

it should not be seen as a mitigating factor more than any other source

of stress should be seen as a mitigating factor. By and large, parents

of people with disabilities are able to take care of their children

without trying to kill them.” –Samantha Crane

Whenever a news story breaks about a parent killing (or trying to murder) a disabled child, reactions to the story are almost as disturbing as the story itself — because

media and blog accounts tend to empathize with the parents,

not the child victims. In fact the children in these cases are almost universally depicted as trigger for their parents’ acts, rather than human beings with feelings, friends,

interests, and rights.

We need to change those conversations.

|

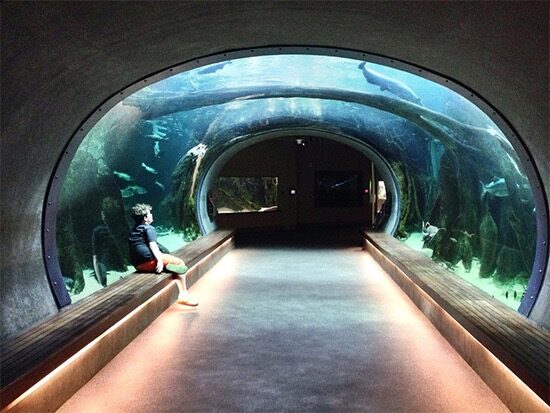

| Photo © Shannon Des Roches Rosa

[image: white teen boy with dark curly hair sitting on a bench in a walk-through aquarium tunnel] |

I want us to be more careful and compassionate when we talk about parents harming their disabled children. I want us to remember who the real victims are. And if we find ourselves empathizing with those parents, I want us to think long and hard about why.

If you identify with a murderer rather than a

murder victim, or if you become upset when people criticize parents who

hurt or kill their disabled kids, then maybe it’s time to think about

how you found yourself in that dangerous mind space and start making

changes to help you, your child, and your family.

It may be that

you come from outside the autism and disability communities, have only

heard negative media messages about how difficult parenting a child with

a disability can be, have never encountered people who believe in your

child just as much as they want to support you. If this is the case,

your attitude is not entirely your fault. But you can find and surround

yourself and your child with community that matters—offline, and on—and with people who want the best for both of you.

It

may be you reject the idea of accepting your child as disabled, because

you believe that mindset means giving up or being in denial. You may

assume parents like me, who constantly speak up about acceptance and understanding

either have “easy” kids or are lying about what our lives are really

like. But that’s not what acceptance means at all, as explained by Real Social Skills:

“Acceptance

creates abilities. Acceptance makes it easier to be happy and to make

good decisions. But acceptance does not solve everything, and it does

not come with an obligation to love absolutely every aspect of being

disabled.”

It may be you can’t stop worrying about what will happen to your child after you die. But most children—disabled, autistic, or not—will and do outlive their parents. Try to reassure yourself by learning about “the different paths a child with special needs can take after graduating from high school,” and investigating what your family’s long-term special needs legal planning options actually are.

It

may be you are participating in a community that, while providing

catharsis and emotional connections you haven’t found elsewhere, is

actually toxic, actually fosters insidious attitudes about parenting

children with disabilities. If the parents you rely on for emotional

support consider such murder attempts “altruistic filicide,”

or justified due to desperation, then it’s time to cut ties. It might

feel like severing a limb, but you need to prioritize your safety and

that of your child by finding parents who will help get you through trauma and crisis, but would not “understand” if you harmed your child.

It

may be you don’t have the services or support you and your child need;

you may even feel like you’re living in a minefield. This is a very

real, not-rare situation, and it’s not limited to parents who refuse to

understand or accommodate their child’s disability. People with disabilities who require intensive supports deserve sufficient resources, and so do their families.

When these services are minimal or unavailable, that is a large-scale

failure on our society’s part. However, insufficient resources don’t explain or justify murder of disabled children, because such

crimes—which are also, frighteningly, not rare—do not actually have lack of services in common.

So please don’t spread the dangerous message that if parents don’t get

enough services, they might kill their autistic or disabled child.

Instead,

parents — like me, like you — need to hear, and believe, that it’s not a failure or shameful to ask for help, and we need to feel safe about doing so. For

our own sake, of course, and also because reaching out protects our kids

as well as ourselves. I’m pretty sure disabled people who survived harrowing, abusive childhoods

would much rather have been raised by supported and supportive parents.

That is one of the reasons so many autistic and disabled adults offer

their insights online—they want our children to have better lives than

they did. As long as parents are respectful, those adults can be a

crucial part of your supportive community.

Parents also need to

hear that when parenting is truly beyond their ability to handle, they

always have options, even if those options break their hearts. They can,

like two of my own friends have, place children in group homes. As I wrote on BlogHer:

“We

need to stop assuming that putting a child into another’s care equals

giving up on that child. We need to stop declaring that when people

relinquish their children, wholly or partially […], it is because the

parents are selfish. We should consider that these parents may be giving

away the part of their soul that will always envelop that child for the child’s sake, not to make the parents’ lives easier.”

And if a parent truly doesn’t know where to turn, they need to know they can call emergency services, like those compiled by autistic writer and parent Paula Durbin-Westby. That call may result in separation

between parent and child—maybe even a permanent separation—but who

wouldn’t prefer a parent and child alive but

living separately by court order, over a murdered child?

It always comes back to finding

the right community, finding friends who want to help you get through

those days. And then the next one. And then the next. Many parents who

feel this way are online, like Ariane Zurcher, who wrote about her relief in finding the support her family needed, and remembering her days of feeling alone and frightened:

“There

is so much we are learning and still have to learn, but we are no

longer alone. We are surrounded by other parents, professionals,

educators and, most importantly, people who share our daughter’s

neurology, those who are Autistic and who continue to share their

experiences with us so that we might better parent our Autistic

daughter.”

Like Ariane, we need to learn to be

careful where we look for help. We need to look to people who value our

kids as much as we do—who will have both our and our kids’ backs during

desperate times.

I often share the We Are Like Your Child checklist for Identifying Sources of Aggression. Itexplains,

from the perspective of people who share my own child’s disability and

neurology, the many, many, many reasons—from communication needs unmet

to medical conditions to sensory overload—that may underlie otherwise

inexplicable violence.

I

think we parents also need to be extra-cautious in how much we reveal,

publicly, about our children’s difficulties, because we don’t want to

give people who neither love nor understand our kids ammunition for devaluing our children’s lives, nor do we want to send the

message that disabled children do not have the same right to privacy

as their non-disabled peers. We need to

help others understand our kids, of course, but from the perspective of

telling the world that they are deserving human beings, rather than

crosses for us to bear and commiserate over. We need to protect our kids

at their most vulnerable and difficult times—even if those are times

when are at our most vulnerable, too.

So find your positive,

supportive people. They’re out there, in safe public and private online

groups, and on mailing lists. Once you’re part of those groups, you can

connect with people who can help you process and problem solve on a

smaller scale, whether through texting, Skype chats, weekly private vent

sessions, therapy, or in wiping tears off each other’s faces before

they fall into our coffee or beers. It’s even okay to lurk in forums, if

you’re not comfortable talking with other people just yet. Just be

careful about what you make public about your family, and who you listen

to. And remember that your community is out there, you just need to

locate it. Your people are waiting for you.

—-

A version of this post originally appeared at BlogHer.com. I’d like to thank the autistic author of the blog Real Social Skills for helping me shape the original post.