Maxfield Sparrow

|

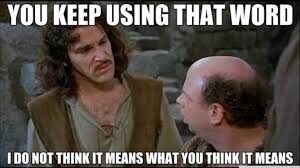

| [image: Screenshot of Inigo Montoya and Vizzini from

the movie The Princess Bride, with white overlaid block text reading, “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.] |

Last week, the San Francisco Autism Society of America (SFASA) held its 16th annual conference at Stanford University. In her opening comments, Jill Escher, the president of SFASA, went through a few words and phrases, claiming to “defuse some autism vocabulary stinkbombs.”

I disagree with so much of what she said about … well, about pretty much everything she talked about. But I want to focus in on one word that I feel she completely misrepresented on so many levels that it was mind-boggling:

Self-advocate

Escher chose to show a 20 second video clip of her son to the audience, to illustrate her lack of understanding of the meaning and expression of self-advocacy. In the course of enacting conservatorship, the court sent a social worker to Escher’s house to investigate the situation and ensure that conservatorship was called-for, and not an abuse. The video clip showed a social worker querying her son in a patronizing, sing-song voice — the sort of syrupy voice that makes small children cringe and should never be used on an adult, whether that adult requires 24/7 lifelong support or not.

“Can you tell me where you live?” the court investigator cooed. She paused and waited while Escher’s son ignored her question. “Can you tell me, when is your birthday?” Again, no response. “He’s non-verbal and non-responsive,” the social worker declared.

The clip ended and Escher announced that this 20 seconds of video was proof that her son is not a self-advocate. She said that calling her son a self-advocate denigrates his reality and, “denigrates those who actually bear the physical, intellectual, financial, and legal responsibility to care for people like this.”

There is so much wrong with what Jill Escher did and said that I’m feeling overwhelmed, trying to decide where to enter this mess.

In no particular order:

- “Self-advocate” is a title that needs to die a quiet death.

- Self advocacy skills are not limited to speech.

- I have watched another Autistic do nearly the same thing as Escher’s son and his silence was an act of self-advocacy.

- Skills of self advocacy come in many forms and accompany many different types and levels of support need. Self advocacy is not an on/off, “you have it or you don’t” sort of thing.

- It’s not a competition.

- Never exploit your children as part of your political argument!

Having planted my entrenching tool in a few different heaps, I am now calm enough to unpack some of those bullet points.

The term “self-advocate” was a useful phrase (it arose in hospital settings where it was applied to patients who became actively involved in their own care), but it has been extended far beyond its initial usefulness, to the point where the phrase has become weaponized. I’m not talking about skills of self advocacy; I’m talking about the noun “self-advocate” when used as a title or label applied to someone.

So often, “helpful” people insist I should not call myself Autistic because, “it’s just a label and doesn’t define you.” But some days it feels like everyone wants to call me a self-advocate (including, ironically, some of those people who wish I would stop calling myself Autistic). I hate re-inventing the wheel, so if you want to know more about why I think the label “self-advocate” is often used as a way to diminish the powerful work of Autistic activists and advocates for others, read my blog post, Don’t Call Me a Self-Advocate.

When “self-advocate” is being used as a euphemism for “highly articulate Autistic activist,” no, Jill Escher is right: during the 20 seconds of video, her son not depicted as being a self-advocate. This is not to say that he will never be articulate or speak out about autism or speak on behalf of other Autistics. I have many friends who do not use their voices to communicate yet their words speak powerfully of our humanity, dignity, and rights. While I would like people to stop calling us self-advocates when we are actually advocating for others, not only for ourselves, I must also pause to recognize some of the tremendous unspoken voices available for you to read: Amy Sequenzia, Emma Zurcher-Long, Tracy Thresher, Larry Bissonette, Barb Rentenbach, Mel Baggs, Tito Mukhopadhyay, Lucy Blackman. While I would like to see the label “self-advocate” go away, the lives and work of the Autistics on this list demonstrate that speech is not required to be a highly articulate Autistic, activist or otherwise.

Twenty seconds of video footage tells us so little about a human being and his complex life. Does Escher’s son have any means of communication at all? What means have been offered to him and how were they presented? So many therapies are “speech-or-nothing.” So many therapies take away AAC devices if an Autistic is caught “playing” with them (imagine if we took away a baby’s voice whenever it babbled and refused to allow it vocal cords until it could commit to only using them for serious communication!) I feel I know so little about Escher’s son from that brief clip, but the main thing I do know is that what separates the young man we see for 20 seconds from Autistics who identify as self-advocates or have the label thrust upon them is communication.

Escher’s son can be in genuine need of 24/7 care and have a high need for a great deal of support while still exhibiting skills of self advocacy or while being a highly articulate activist or advocate for others. Someone else (myself, for example) can have much lower support needs (although you must not fool yourself into believing I have no need for support and assistance at all. Just because my needs are lower does not mean they are low) and be extremely articulate (particularly in writing) and also exhibit skills of self advocacy. My self advocacy and Escher’s son’s do not look the same, but we both have self advocacy skills and we both deserve the supports we each need, despite how different we are.

What is being denied to Escher’s son when his mother says he is in no way a self-advocate is a sense of agency and autonomy. With 20 seconds of video and the claim that he is not a self-advocate, his mother not only puts him on display as little more than an illustration for her political and personal beliefs about autism, she sweeps his agency out the door. Because if he is hungry and points at food and makes urgent grunting sounds yet Escher’s son is not a self-advocate, what is he doing? Surely he is not asking someone to feed him because that would be an act of self advocacy. So he must be misbehaving or, worse, engaging in pointless behaviors. When Escher’s son’s hunger continues, combined now with the frustration at his very real lack of agency since his clear request for food was denied and ignored, perhaps he will become so angry that he punches a hole in the wall. Now he is dangerously violent and must be restrained for his own good and to preserve the safety of others.

This is not just wild speculation on my part. While I do not know Escher’s son, I do know scores of other Autistics and I have heard and read their stories and watched these types of scenarios play out in their daily lives. So many Autistics are grossly mishandled by people because they are assumed to have no communication or skills of self advocacy. They are denied agency in their lives and their actions are misinterpreted in harmful ways that lead only to a continual decline in their quality of life.

Who, in frustration at being told they were not really communicating, would not choose to detach from the world? Why would you want to try to be responsive to a world of people who don’t understand you and seem not to be even trying? Who, in anger at having their agency stripped from them, would not resort to force to try to get their needs met? Who among us would not want to express their painful sense of injustice by lashing out at a world that is confusing, painful, and eternally disappointing?

I have a friend who is five years old and Autistic. I watched one day as an evaluator came to his house to test him. The evaluator spoke with the same syrupy voice as Escher’s son’s examiner, and I watched my young friend respond to her with clearly visible disgust. My friend did not answer her questions and refused to do the things she asked him to do, even though I knew he could do many of those things quite well. He is a very clever young man but all the evaluator saw was a non-responsive, defiant, angry child. She tried her usual threats and manipulations but he saw through them and she was quickly forced to pack her bag and leave. My friend’s refusal to engage with the condescending examiner was an act of self advocacy and I am proud of him for maintaining strong boundaries and refusing to be forced to do things that feel wrong and insulting to him.

When one of my friend’s parents told the evaluator that my friend did not like her, she was genuinely shocked. I don’t think she understood her own tone of voice and how triggering it can be to people who are regularly treated as incompetent and denied agency in their own lives. She thought she was friendly and fun and could not grasp why someone would be put off by her approach. It made me sad because she cannot change what she is not able to see.

I think Escher is similarly confused. She called the court evaluator a nice lady and probably doesn’t understand how demeaning the evaluator’s voice was. If I were Escher’s son, I would not want to respond to that voice, whether I could speak or not. And I’m trying to explain how it is that the examiner’s patronizing approach and Jill Escher’s refusal to consider the possibility that her son could be a self-advocate (despite Escher’s claim that many people tell her that her son is a self-advocate) are cut from the same cloth — both are infantilizing presumptions of a lack of competence that imply or require a denial of agency.

Jill Escher exploits her son’s image and denies his agency as part of a political stance in which she views people like me and our families as being in direct competition with people like her son and their families. Escher is viewing supports as a zero-sum game in which any amount of money, medical care, or time I get is stolen from the money, medical care, and time that Escher’s son needs. By emphasizing that her son is not a self-advocate, she tries to set up a dichotomy in which people like me — people she would call self-advocates — do not need any help in life and do not deserve any benefits or supports while people like Escher’s son — so clearly not a self-advocate that 20 seconds are all we require in order to confirm her belief — needs all the help and all the benefits and supports.

I need what I need. Escher’s son needs what he needs. And all of us, our entire society, needs to accept that and work to meet the unmet needs of all Disabled people, regardless of the type of disability or the level of support we require. It’s not about some of us being written off as “self-advocates” or some of us being written off as being incapable of self advocacy. That’s just the same song with different words. If you aren’t familiar with the tune, go read anything any Autistic has written about “function labels.”

Escher is singing the familiar refrain of “my son is so low functioning! So please, world, take care of him when I am gone. Those people who can write or speak about their autism are so high functioning! Don’t let them steal what my son needs to survive!” It’s the second verse of the song but don’t let the lyrics fool you; it’s the same tired melody that hurts us all.